Is the Fed raising rates because of the "strong U.S. economy", or are they trying to get some wiggle room and slow down the market?

Consider this..

GubbmintCheese

Thoughts that require more than 140 characters from that nut @gubbmintcheese

Sunday, March 11, 2018

Using statistics to see growth, even when it's not there

“Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it

will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses

slowly, one by one.”

Ever

since the end of the “Great Financial Crisis” in June 2009, central bankers and

financial analysts have been sifting through each newly released economic

report, carefully searching for signs of a sustainable recovery so that they

can confidently declare “Happy Days Are Here Again” (a song ironically written

in 1929, just before the Great Depression). While Canadian and U.S. Gross

Domestic Product (or GDP, which measures the growth of an economy) have

certainly improved since the recession of 2009, neither economy has really

’bounced back’ with the same magnitude and strength of previous recoveries. In

fact, while the economic expansion in the United States is approaching a record

with regards to duration, the rates of growth have

been some of the weakest and most anemic on record. Unfortunately, persistently

weak economic data does not deter financial analysts (whose job it is to be

glowingly optimistic) from misrepresenting certain data points to support their

forecasts, calling for buoyant recovery brewing just beyond the horizon.

To quote

former British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli,

“There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned

lies, and statistics.”

As

someone who immerses himself in macroeconomic data seven days a week (an

embarrassing confession, I will admit), I get very frustrated when I read

economic forecasts that are obviously relying on cherry picked data to support

a blatantly biased bullish narrative (because quite honestly, being bullish is

great for business). From my perspective, an economic forecast should simply

reflect what “is” going on versus what we “wished” was happening. It’s even

more frustrating, however, when the stock and bond markets fall for a flimsily

supported bullish narrative without at least taking time to look under the hood

at exactly how the forecast was derived.

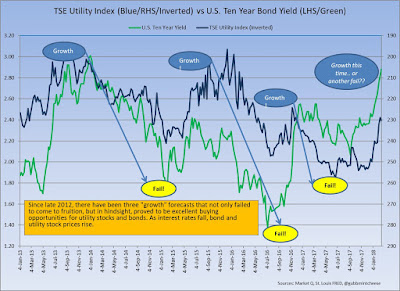

We’ve

seen the markets buy into a bullish recovery three separate times since 2012,

and it appears as though we are working on “false alarm number four” today. In

the three previous occurrences, an optimistic narrative (from a credible

source, the Federal Reserve) resulted in market expectations of a strong

increase in economic activity, which in turn led to the presumption of higher

wages, rising inflation and ultimately rising interest rates. In this

situation, bond and utility prices fall in anticipation of rising rates,

and subsequently, yields rise. Over time, however, the expected growth in these

three previous bullish cases was not forthcoming, and shortly thereafter bond

and utility prices not only recovered previous losses, but outperformed the

overall market quite handsomely.

The chart

below shows three separate occasions since late 2012 where the markets

responded to forecasts for a strong rally in U.S. economic growth as well as

the fourth case that is as of yet unresolved. In each of these three cases, you

can see interest rates increased sharply which in turn caused bond and utility

share prices (as measured by the TSE Utility Index) to decline. However, as

detailed above, the jump in economic activity proved not

forthcoming. Enthusiasm for the growth story eventually faded, and interest rates start falling once again. In all three cases bonds and utility stocks

enjoyed a very strong recovery.

The next

question for us then becomes, “What do we do about the current

expectation for future growth?” For me, the answer here is the same as it was for

growth narratives one to three, do nothing.

I say “do

nothing” because I’ve taken the time to tear into how the current bullish

forecast has been derived. In doing so, I recognized quite early on that calls

for an economic growth spurt started to hit the headlines in late September

2017, immediately after Hurricanes Harvey and Irma made landfall and devastated

regions of the Southern U.S. and Puerto Rico. Hurricane Harvey was the first

major hurricane to make landfall in the U.S. since 2005, and inflicted

approximately $108 billion in damages, while Irma’s damage (which made landfall

two weeks later) was estimated to be $83 billion. Obviously, huge sums of money

were spent to rebuild portions of the Southern U.S. from these two devastating

disasters (approximately $200B). Spending $200 billion in an economy in such a

short amount of time would undoubtedly lead to a very measurable jump in

economic activity. However, unlike a sustainable recovery, these hurricane

related expenditures were one-offs, and would eventually die down after the

rebuilding was complete. Unfortunately, some economists and news outlets jumped

on this economic bump and started to extrapolate a story of economic recovery.

For example, look at the leading headline from a CNBC story in January 2018

that declared, “Strongest holiday sales since Great Recession, up 5.5% topping

industry’s forecasts.” If you read the story further you will see the sector

that recorded the biggest jump in sales was building materials and supply

stores with 8.1% growth. Building materials and supply store sales are part of

Christmas sales? Ask yourself, when was the last time you got a cinder block or

a sheet of plywood for your significant other for Christmas? This is simply a

case of twisting statistics to report something that was wished true, rather

than what was actually true.

Another

key component of our current growth narrative is that wages are beginning to

show signs of improvement. A February 2018 CNN Money article boasted

“America gets a raise: Wage growth fastest since 2009.” The article goes on to

say “The unemployment rate stayed at 4.1%, the lowest since 2000, the Labor

Department said Friday. Wage growth has been the last major measure to make

meaningful progress since the end of the Great Recession.” And, finally, the

article states, “Economists say it’s time to take note of how strong, or tight,

the U.S. job market is.”

While it

is true that the current rate of unemployment in the United States is a very

low 4.1%, which (if accepted at face value) should suggest a very strong

job market, the reality is not quite as straightforward. To get a better understanding

of this we need to dig into how this statistic is derived.

The

unemployment rate measures “the current number of people who are unemployed”

against “the number of people who are in the labour force.” A more indicative figure

is the civilian employment population ratio. It is calculated by dividing the

number of people employed by the total number of people of working age. What is

interesting is that if you look at the relationship between the civilian

employment population ratio and the official unemployment rate you will see a

very large disconnect between the two that started at the bottom of the Great

Recession in 2009.

We can

see this disconnect in another comparison, between the unemployment rate and

average hourly earnings. In the chart below, there appears to be a very close

historical correlation between average hourly earnings and the unemployment

rate in the United States that seemed to break just after the crisis ended in

2009. Once again, I would suggest "opportunistic economists" are using the

unemployment rate to make overly optimistic forecasts about future economic

growth.

The

charts above and below (coupled with about two dozen more that I maintain on a

regular basis) leave me with the opinion that the call for strong U.S. economic

growth and persistently rising interest rates is yet another false alarm. As

such, I’m not selling any of the bonds and utility companies that I hold, even though prices of both have fallen since September. Instead, I am

using this as a buying opportunity for these great investments as I believe

market participants will realize (slowly and one by one) that growth is once

again not forthcoming and instead, will realize that the market fell once more for another false

alarm, compliments of misrepresented facts through statistics. Benjamin

Disraeli would be impressed.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)